How VR Simulation Can Improve Maternal Morbidity and Mortality Rates in the U.S.

Published December 21, 2022

By Martha Levine:

My Experience in A Moderate-Sized Healthcare System

As a perinatal and NICU enterprise nurse educator for a moderate-sized healthcare system, I witnessed firsthand how challenging it was to attempt to create enterprise-wide or system-level practice guidelines in obstetrics. In my current role as a nurse educator for Health Scholars, I have the privilege to work with nurse managers, nurse and physician educators, and healthcare risk quality and safety professionals from across the country. A common and recurrent theme I hear from healthcare professionals is that the inconsistent or inadequate use of evidence-based practice guidelines is a contributing factor to poor maternal/child outcomes.

It has been well acknowledged that modern healthcare is very complex.

Factors that contribute to this complexity include continuously evolving research and practice recommendations, short staffing, limited resources available for clinicians, and decreasing institutional support for continuing education and training. There is also an increased pressure to see more patients more quickly and “to do more with less,” meanwhile, patients are having increasingly complex comorbidities. Finally, our healthcare system has been deeply fatigued by the recent and ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Clinicians are working so hard to provide high-quality, cost-effective, safe care for their patients, but often, despite their best intentions, clinicians are not practicing with the best evidence-based guidelines available.

Why is That?

My review of the literature found that even though healthcare professionals across specialties value and support the idea of using evidence-based practice guidelines, there are significant barriers to implementing them. Several studies even found that research findings were rarely used in clinical decision-making practice.

Some of the barriers identified were:

- A lack of knowledge and skills about how to search for, evaluate, and apply new research evidence

- Not enough resources and training for continuing education

- Time management and cost concerns

- Change fatigue which causes a lack of motivation to implement new evidence-based practices

Some additional barriers identified in the literature were a workplace culture that didn’t support the implementation of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines, and the concern that some clinicians actually consider guidelines to be a threat to good clinical practice. To explain it another way, some physicians reported feeling concerned that a rigid application of guidelines would not acknowledge the value of their clinical experience and expertise and would also compromise individualized patient care.

In the past few decades, healthcare has been forced to take a long, hard look at our often poor performance history and outcomes data. Beginning in the 1990s with the seminal Institute of Medicine report “To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System,” there has been a great deal of focus on high-reliability organizations such as aviation and high-stakes construction projects, like skyscrapers. Despite a great deal of research and changes that support highly reliable organizations in healthcare, the U.S. still has unacceptably poor maternal morbidity and mortality outcomes for minority populations, specifically with health disparities for Black, Native American, and Alaskan Native birthing people.

The Checklist Manifesto

As part of my graduate evidenced-based practice course, I was encouraged to read The Checklist Manifesto by Atul Gawande. Dr. Gawande, a surgeon, argues that the vast majority of errors in healthcare occur because clinicians inadequately apply what we know. Dr. Gawande is a gifted storyteller and uses a series of medical stories that demonstrate how routine surgeries have become so complicated and that errors are virtually inevitable. In the pressure and stress of a surgical procedure, otherwise competent doctors are not immune from making human errors. It’s simply too easy to miss a critical step, forget to ask for a critical piece of information, or always be prepared for any possible contingency. Dr. Gawande’s research team visited with leaders in aviation and construction teams that built skyscrapers and came up with an idea that was revolutionary for that time. Dr. Gawande proposed that all experts, including healthcare professionals, need checklists

Checklists are essential step-by-step written guides that walk through the critical steps for complex procedures. Dr. Gawande further proposed that we should reevaluate how we define expertise. He suggested that even experts need help and that if we are going to improve the quality of our healthcare system, we must begin by allowing experts to have the humility to concede that they need help. Even though The Checklist Manifesto was written 13 years ago and checklist-style practice guidelines are more widely accepted in healthcare practice, I would argue that obstetrics and gynecology have been slower than average to adopt these types of guidelines. There are various reasons for this hesitancy in obstetrics, including valid reasons, such as the ethical challenges associated with conducting research on pregnant and laboring patients, particularly the research “gold standard” – the Randomized Controlled Trial. When considering obstetrics/gynecology, I would argue that there is a great deal more subjectivity involved with everyday practice when compared to other specialties. The processes of labor and birth are certainly not identical across the population of birthing people, and a one-size fits all approach is clearly not appropriate for every person during their labor/birth.

Allowing for individualized plans of care that address patient and provider concerns certainly needs to be addressed when developing practice guidelines. Some of the most commonly used guidelines were developed by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative (CMQCC). These guidelines certainly allow clinicians to use their professional expertise when selecting medications and the order of some of the steps within the guardrails of the overall recommendations. However, should there be consideration given to whether having too much variation can diminish the intent and impact of having a guideline in the first place? I would argue that having too much leeway in practice guidelines has the potential to negatively impact racial disparities in obstetric care.

Racial Disparities and Implicit Bias

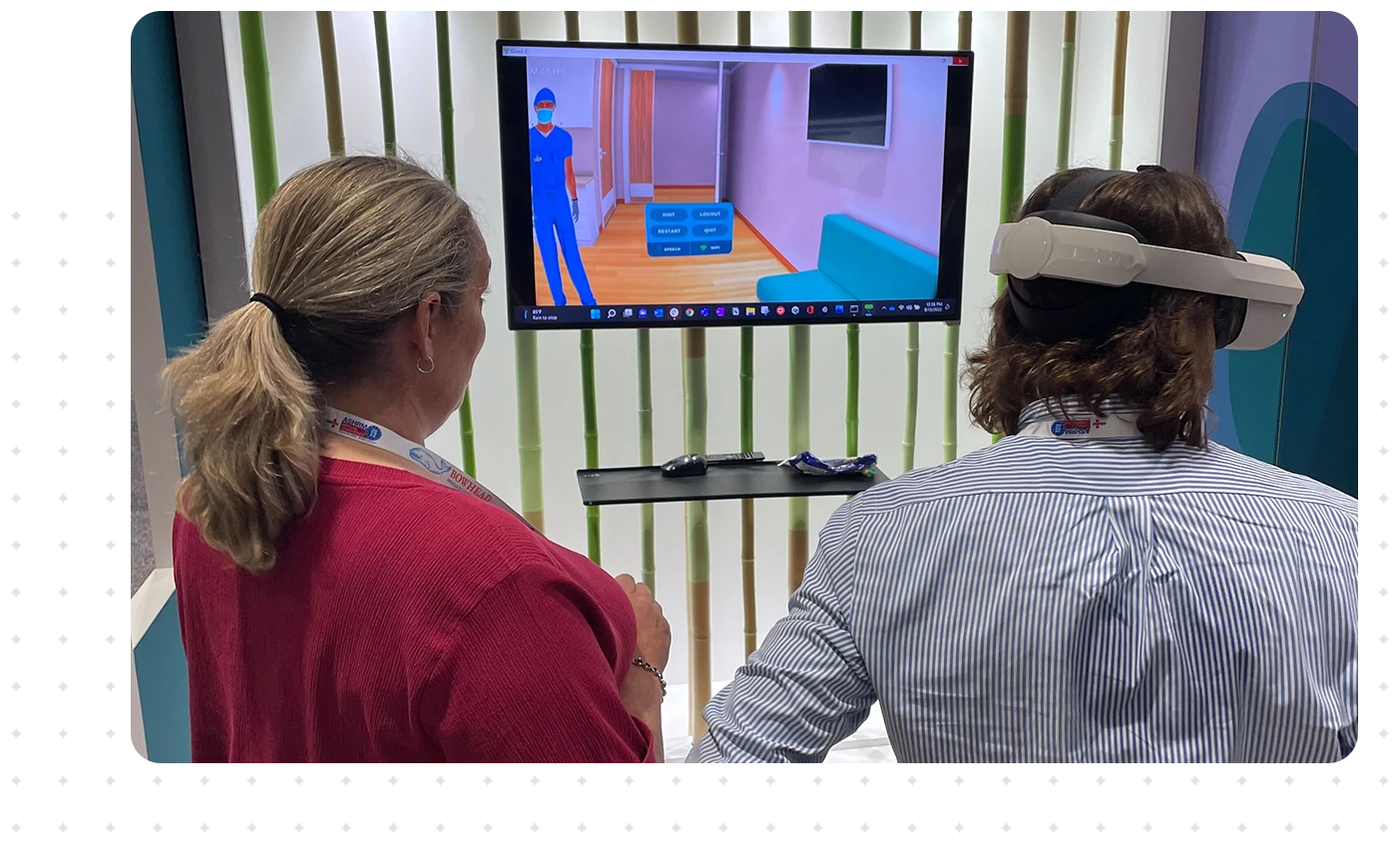

Racial disparities in healthcare are believed to be attributable largely due to implicit bias. One of the education methods that has been shown to reduce the likelihood of implicit biases being activated is to use repetitive, protocol/guideline-driven training. These types of training methods focus on identifying and responding early to objective warning signs and symptoms. Furthermore, educational research has demonstrated that training in high-stakes clinical situations is best accomplished and retained through experience-based training. Using Health Scholar’s virtual reality simulation is effective, repeatable, experiential, self-directed, and requires fewer resources than traditional simulation.

Health Scholar’s virtual reality applications are designed to allow the user to practice evidence-based healthcare protocols in the team leader role. The user in the headset uses their voice to direct the actions of a multidisciplinary healthcare team and uses a patent-pending artificial intelligence voice technology. Rehearsing clinical practice guidelines as a team leader is a common educational strategy in healthcare. The team leader role allows the learner to demonstrate their knowledge and situational awareness of the whole clinical picture, and to practice high-quality multidisciplinary team communication. Clinical practice guidelines are objective and reinforce the early warning signs of clinical emergencies.

I believe that the frequent, repetitive practice of guidelines can improve individual healthcare providers’ knowledge and confidence in their ability to react quickly and accurately.

Having the entire healthcare team practice encourages the development of a shared mental model so that when a real-life emergency arises, the whole team knows what to expect, and how to react. Frequent, consistent, repetition of the training creates muscle memory and ingrains the critical processes of the practice guidelines, enabling healthcare professionals to react quickly and appropriately. Teaching methods that access the affective learning domain have been shown to be more engaging to learners, improve retention, and make concepts more “sticky.” I have seen it time and time again as a nurse educator – using the affective domain to connect to actual human experiences makes all the difference in learning. This is true whether you are impacted emotionally by hearing a powerful story, participating in a simulation experience, from an actual clinical experience, or through virtual reality.

Virtual reality provides another way to experience simulation that achieves many of the same goals and benefits. Furthermore, Health Scholar’s virtual reality simulations are portable, easily accessible, and can be done quickly with fewer resources. Finally, to quote Albert Einstein “The only source of knowledge is experience.”

How Can Health Scholars Help?

Interested in how Health Scholars can help support your nurse retention efforts? Contact us to start a conversation.